Chevron's competitive advantage comes from a combination of massive scale, integrated operations, a low-cost asset base, and decades of infrastructure investment that competitors can't easily replicate. The Chevron moat isn't built on any single factor. It's the result of upstream reserves in premium basins, a global downstream network, and the financial discipline to fund long-cycle projects that smaller players simply can't afford. Understanding CVX's competitive position means looking at how all these pieces lock together.

Key takeaways

- Chevron's moat rests primarily on cost advantages from tier-one acreage in the Permian Basin and Kazakhstan, plus integrated operations that smooth out commodity cycles

- Scale gives Chevron bargaining power in procurement, joint ventures, and capital markets that mid-cap producers can't match

- Switching costs are low for oil and gas buyers, but Chevron's infrastructure lock-in on the supply side creates durable barriers to entry

- The biggest threats to Chevron's competitive position are the energy transition, regulatory risk, and reserve replacement over the next decade

- Compared to Exxon and Shell, Chevron trades a smaller revenue base for arguably better capital discipline and a cleaner balance sheet

What is Chevron's moat, exactly?

When investors talk about a company's moat, they mean the structural advantages that protect profits from competition over time. For Chevron, the moat isn't the kind you see with software companies or consumer brands. Nobody picks gasoline based on loyalty the way they pick an iPhone. Instead, the Chevron moat is almost entirely about cost position and scale.

Economic moat: A durable competitive advantage that allows a company to earn returns above its cost of capital for an extended period. For energy companies, moats typically come from low-cost reserves, infrastructure, and scale rather than brand loyalty or network effects.

Chevron controls acreage in some of the world's lowest-cost production basins. Its Permian Basin position alone gives it access to decades of drilling inventory at breakeven costs well below many competitors. Add in the Tengiz field in Kazakhstan and Australian LNG assets, and you have a portfolio where Chevron can remain profitable even when oil prices drop to levels that force higher-cost producers to shut in wells.

That's the core of it. In a commodity business, the company that produces at the lowest cost per barrel wins. Not every quarter, but over full cycles. You can explore Chevron's full research profile to dig into how these assets show up in the financials.

How does Chevron's integrated model create a competitive advantage?

Chevron isn't just a drilling company. It's an integrated oil major, which means it operates across the entire value chain: exploration and production (upstream), refining and chemicals (downstream), and midstream pipelines and logistics. This integration is a genuine structural advantage, and here's why.

When crude oil prices fall, upstream profits shrink. But lower crude prices often mean better refining margins because input costs drop while fuel demand stays relatively stable. Chevron's downstream operations act as a natural hedge. The reverse happens when crude prices spike. This doesn't eliminate cyclicality, but it narrows the range of outcomes. Chevron's earnings don't swing as violently as a pure-play exploration company's would.

Integration also reduces transaction costs. Chevron moves its own crude through its own pipelines to its own refineries. It doesn't need to negotiate spot shipping rates or worry about third-party pipeline capacity during bottlenecks. Over time, those savings compound.

Does integration matter as much as it used to?

There's a fair debate here. Some investors argue that pure-play E&P companies with great acreage can outperform integrated majors in a bull market, and they're right. Integration is a defensive advantage more than an offensive one. It protects downside more than it amplifies upside. For investors focused on risk-adjusted returns over full commodity cycles, that matters a lot. For momentum traders, less so.

Chevron's cost position vs. Exxon and Shell

Comparing CVX's competitive position to its closest peers reveals some interesting differences. All three companies are integrated majors with global operations, but they've made different strategic bets.

Chevron vs. Exxon: Exxon is larger by revenue and production volume. It has a bigger refining footprint and a more aggressive acquisition strategy. But Chevron has historically carried less debt and maintained tighter capital discipline. Chevron's debt-to-equity ratio has generally been lower than Exxon's, giving it more flexibility during downturns. On a per-barrel production cost basis, the two are close, though Exxon's Guyana assets have shifted its cost curve favorably in recent years.

Chevron vs. Shell: Shell made a bigger pivot toward natural gas and LNG earlier than Chevron and has invested more heavily in renewable energy. That diversification could be a long-term advantage if the energy transition accelerates, but it's also diluted Shell's upstream returns in the near term. Chevron's more focused portfolio tends to generate higher returns on capital employed when oil prices are in a normal range.

None of these companies has a clear knockout advantage over the others. It's more about which trade-offs you prefer. Chevron's edge is balance sheet strength and capital discipline. Exxon's edge is sheer scale. Shell's edge is energy transition positioning.

What types of moat does Chevron actually have?

Let's run through the classic moat categories and see which ones apply to Chevron's competitive advantage.

Cost advantages: This is Chevron's strongest moat source. Low-cost Permian acreage, legacy assets with sunk infrastructure, and efficient operations give Chevron a cost structure that's hard to replicate. A new entrant would need to spend billions on land, drilling, and pipeline infrastructure just to get to the starting line.

Scale: Chevron's size allows it to negotiate better terms with service companies, access cheaper capital, and absorb regulatory costs that would overwhelm smaller operators. Scale alone isn't a moat if everyone has it, but in oil and gas, the gap between supermajors and the next tier is enormous.

Switching costs: Minimal on the demand side. Gasoline is gasoline. But on the supply side, Chevron's long-term contracts, joint venture positions, and government concessions create meaningful lock-in. Once you've invested billions in a 30-year production-sharing agreement in Kazakhstan, you're not walking away.

Brand power: Limited. Chevron has consumer brand recognition at the gas pump, but it doesn't drive pricing power. Nobody pays more for Chevron gasoline because of the logo.

Network effects: Essentially none. Oil and gas is a commodity market, not a platform business.

Switching costs (supply-side): In capital-intensive industries, the massive upfront investment in infrastructure, permits, and long-term contracts creates barriers that lock in the producer, not the customer. This is distinct from demand-side switching costs seen in software or banking.

How durable is Chevron's moat?

Durability is where things get more complicated. Chevron's moat is real, but it faces genuine threats that investors should factor into any long-term thesis.

Reserve replacement: Oil and gas companies deplete their reserves every year through production. Chevron needs to continuously find or acquire new reserves just to stay in place. If acquisition costs rise or exploration results disappoint, the cost advantage can erode over time. This is a treadmill that every energy major runs on.

Energy transition: The long-term shift toward electrification and renewables is a structural headwind for all fossil fuel producers. Chevron has invested in lower-carbon technologies like hydrogen and carbon capture, but these are small relative to its core oil and gas business. The question isn't whether the transition will happen, but how fast. A gradual transition over 30+ years gives Chevron time to adapt. A rapid one compresses the timeline for monetizing existing reserves.

Regulatory and political risk: Chevron operates in countries with varying levels of political stability. Government renegotiation of production-sharing contracts, windfall taxes, and environmental regulations can all chip away at returns. This isn't unique to Chevron, but it's a reminder that the moat depends partly on factors outside the company's control.

Technology disruption: Advances in drilling technology, like horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, democratized U.S. shale production. Similar breakthroughs could lower barriers to entry in other basins. Chevron benefits from being an early adopter of new technology, but it can't prevent others from catching up.

On balance, Chevron's moat is durable but not impregnable. The cost advantages and scale are likely to persist for at least a decade. The bigger question marks are further out, tied to how quickly the energy landscape shifts.

What threats could weaken CVX's competitive position?

Beyond the macro risks above, a few company-specific vulnerabilities are worth flagging.

- Acquisition integration risk: Large deals carry execution risk. Overpaying for reserves or failing to capture synergies can destroy value quickly in a cyclical industry.

- Capital allocation missteps: Chevron's track record on capital discipline is strong, but one or two bad megaprojects can wipe out years of returns. Deep-water and LNG projects are particularly prone to cost overruns.

- Permian Basin concentration: Chevron's heavy reliance on the Permian is a strength when that basin is performing, but it also creates geographic concentration risk. Regulatory changes in Texas or New Mexico, or unexpected geological issues, could disproportionately impact Chevron compared to more diversified producers.

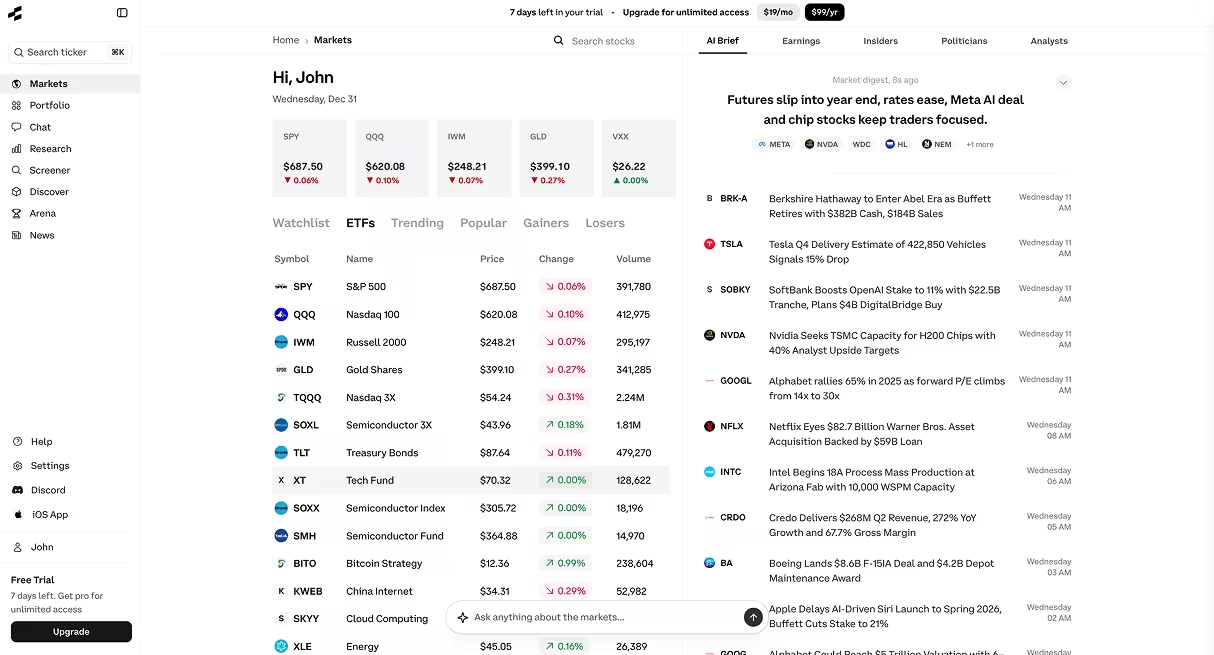

If you want to stress-test these risks against Chevron's financials, the Rallies AI Research Assistant can help you run scenario-based analysis on specific risk factors.

How to evaluate Chevron's competitive advantage yourself

If you're researching CVX's competitive position on your own, here's a practical framework to work through.

- Compare production costs per barrel: Look at Chevron's upstream operating cost per BOE (barrel of oil equivalent) relative to peers. Lower is better, and consistency across cycles matters more than any single quarter.

- Check reserve replacement ratios: Is Chevron finding or acquiring enough new reserves to offset production? A ratio consistently below 100% signals a depleting asset base.

- Evaluate return on capital employed (ROCE): This tells you how efficiently Chevron turns invested capital into profits. Compare it against Exxon, Shell, and mid-cap E&P companies to see if the integrated model actually delivers superior returns.

- Assess balance sheet strength: Debt-to-equity and net debt-to-EBITDA ratios reveal how much financial flexibility Chevron has during downturns. This flexibility is part of the moat.

- Read the capital allocation framework: How does management prioritize dividends, buybacks, debt reduction, and reinvestment? Discipline here separates the best energy companies from the rest.

You can pull up Chevron's key financial metrics on the CVX stock page and use the Rallies stock screener to compare these metrics across the energy sector.

Try it yourself

Want to run this kind of analysis on your own? Copy any of these prompts and paste them into the Rallies AI Research Assistant:

- What gives Chevron its competitive advantage in the oil and gas industry, and how durable is that moat compared to other energy majors like Exxon or Shell?

- What's Chevron's competitive moat? What makes it hard for competitors to take their market share?

- How does Chevron's return on capital employed compare to Exxon and Shell over full commodity cycles, and what does that tell us about moat quality?

Frequently asked questions

What is Chevron's moat?

Chevron's moat is primarily a cost advantage built on low-cost production assets in the Permian Basin and Kazakhstan, integrated upstream and downstream operations, and the scale to negotiate favorable terms across its supply chain. These structural advantages allow Chevron to earn positive returns even during periods of low commodity prices when higher-cost producers struggle to break even.

How does CVX's competitive position compare to other oil majors?

CVX's competitive position relative to Exxon and Shell is strong on capital discipline and balance sheet strength. Exxon has an edge in total production scale, while Shell is more diversified into natural gas and renewables. Chevron tends to generate competitive returns on capital employed while maintaining lower leverage, which gives it more resilience during commodity downturns.

What is Chevron's biggest competitive advantage?

Chevron's biggest competitive advantage is its low-cost production base combined with financial discipline. Controlling tier-one acreage with decades of drilling inventory means Chevron can produce profitably at price levels that would force many competitors to cut production. This cost position is reinforced by scale and integrated operations across the value chain.

Is Chevron's moat threatened by the energy transition?

The energy transition is a long-term structural risk for all fossil fuel producers, including Chevron. The timeline matters enormously. A gradual transition over several decades would allow Chevron to monetize its existing reserves and reinvest cash flows into lower-carbon businesses. A faster-than-expected transition could strand some reserves and compress the period during which Chevron's oil and gas assets generate strong returns.

Does Chevron have pricing power?

Chevron does not have traditional pricing power because oil and gas are globally traded commodities with prices set by supply and demand. However, Chevron's low production costs give it what you might call "margin power." It earns higher margins than higher-cost producers at any given commodity price. That's the functional equivalent of pricing power in a commodity business.

What could erode Chevron's competitive advantage over time?

The main risks to Chevron's competitive advantage include failure to replace depleting reserves at reasonable costs, government renegotiation of production contracts, regulatory tightening in key operating regions, and technological advances that lower barriers to entry for new competitors. Capital allocation missteps, like overpaying for acquisitions or mismanaging megaprojects, could also damage returns and weaken the moat from the inside.

Bottom line

Chevron's competitive advantage is real and rooted in tangible assets: low-cost reserves, integrated operations, scale, and financial discipline. It's not flashy, and it won't show up in a catchy brand slogan. But in a commodity business where the low-cost producer wins over time, Chevron's moat is among the most durable in the energy sector. The key risks are long-dated and tied to the energy transition, reserve replacement, and political factors that affect the entire industry.

If you're building an investment thesis around energy stocks, understanding moat quality is a good starting point. For more frameworks on evaluating competitive position and stock fundamentals, explore the stock analysis guides on Rallies.ai.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice, financial advice, trading advice, or any other type of advice. Rallies.ai does not recommend that any security, portfolio of securities, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. All investments involve risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Before making any investment decision, consult with a qualified financial advisor and conduct your own research.

Written by Gav Blaxberg, CEO of WOLF Financial and Co-Founder of Rallies.ai.